Why Community Motive?

The term, community motive, is a direct response to excessive profit motive. Before defining the term, there are a few things to understand.

In ideal, competitive markets, the profit motive pushes businesses to learn about their customers and provide better services. However, the profit motive, like many things, can be taken too far.

When business leaders, seeking to maintain their profit advantages, drive out smaller competitors, industries can become dominated by a few companies. Such leaders can make decisions (e.g., offshoring, automation) that devastate communities, like in the Rust Belt. Other businesses expand aggressively, crowding out smaller local businesses with deep roots in a community.

Financial institutions back many of these decisions. These institutions’ investments provide businesses the ability to purchase equipment, hire talent, acquire competitors, and so forth. In return, financial institutions get a stake in future profits.

And where do the profits come from? From you, the individual consumer. To be profitable, these businesses need you to purchase their goods and services, often locking you into a particular technology, a monthly pricing plan, etc. It can feel like we are always being targeted by advertisements. Some of these technologies are useful to us, and sometimes it feels like we cannot live a decent life without them: online shopping platforms, ride-hailing services, meal delivery, smart-home assistants. There are always new things being pushed on to us.

What I object to, is the craze for machinery, not machinery as such. The craze is for what they call labour-saving machinery. Men go on ‘saving labour’, until thousands are without work and thrown on the open streets to die of starvation. I want to save time and labour, not for a fraction of mankind, but for all; I want the concentration of wealth, not in the hands of a few, but in the hands of all. Today machinery merely helps a few to ride on the back of millions. The impetus behind it all is not the philanthropy to save labour, but greed. It is against this constitution of things that I am fighting with all my might.” (Mahatma Gandhi)

What’s wrong with this system?

You might be thinking that, while these technologies help our daily lives, there’s something wrong about businesses and financial institutions encouraging new or continuing payments from us or locking us into buying their goods. You can go out there and demand change and protest the system.

But there’s a chance you’re benefitting from this system. Of course, if you work for one of these institutions, then their profits feed into your earnings. But, even if you don’t work for these companies, you benefit if you have a 401k or other investments in the stock market. Your retirement savings grow along with publicly-traded companies’ profits.

If the companies in your portfolio missed their targets for selling goods and services, their stock value would decline and so would the value of your portfolio. While many decry the practices of many of these companies, many unknowingly benefit from their behavior and would be upset if retirement savings were affected.

If you have retirement investments, this situation is not your fault—in our society you need those savings to live a dignified life as an elderly person.

Governments also benefit from the profits earned by financial institutions. When the federal government lacks sufficient revenues (runs a deficit), it issues debt, essentially borrowing money from the financial institutions (primary dealers) that use their revenues to purchase that debt. Primary dealers profit when they resell those debts with a mark-up. Ultimately, government debts are repaid with our tax revenues.

What does this financial system lead to?

To reiterate, profits depend on our purchases. These purchases (consumption) contribute to the national accounting of gross domestic product, or GDP. One simplified way of calculating GDP is to add up consumption (household purchases of final goods), investment (what businesses spend on equipment, software, etc.), government expenditures on final goods, and net exports (total exports minus total imports).

Consumption is often the largest component of GDP. Almost all governments have the goal of growing GDP. Growing GDP is synonymous with economic growth.

Why do governments have a goal of growing GDP? It seems strange to care so much about a statistical exercise. Most politicians would struggle to articulate why it is so important to grow GDP per se, but most people have an intuitive sense of economic growth. Most people equate recessions with hard times, and during these times there are negative effects on well-being.

Recessions can be bad for governments since they lower consumption, which lowers tax revenues that governments need to pay for expenditures and pay off debts. Recessions negatively impact household savings, particularly retirement savings invested in the stock market. To get out of recessions, most governments try to stimulate consumer confidence to increase consumer purchases.

Planetary Boundaries

So why not just keep growing GDP? There are material costs to our consumption that harm the planet. When people purchase a bigger house, a new car, the latest smartphone, an overseas vacation, etc., there are material costs. Such costs include the disposal of existing items, the creation of the new item, packaging, transport, and so forth.

A lot of attention is paid to cutting greenhouse gas emissions, and that is important. But cutting GHG is like assuming getting more sleep will make you healthier. That is necessary but not sufficient. More sleep is good, but many people also need to exercise and watch their diet.

For the environment, it is important to cut GHG, but it is also important to reduce our material impacts. While it may be possible to decouple GHG emissions for our consumption (but evidence is mixed), our levels of consumption continue to add chemicals and waste materials to our natural environment. Given the uncertainty around decoupling emissions from economic growth, it would be risky to assume that such absolute decoupling is likely.

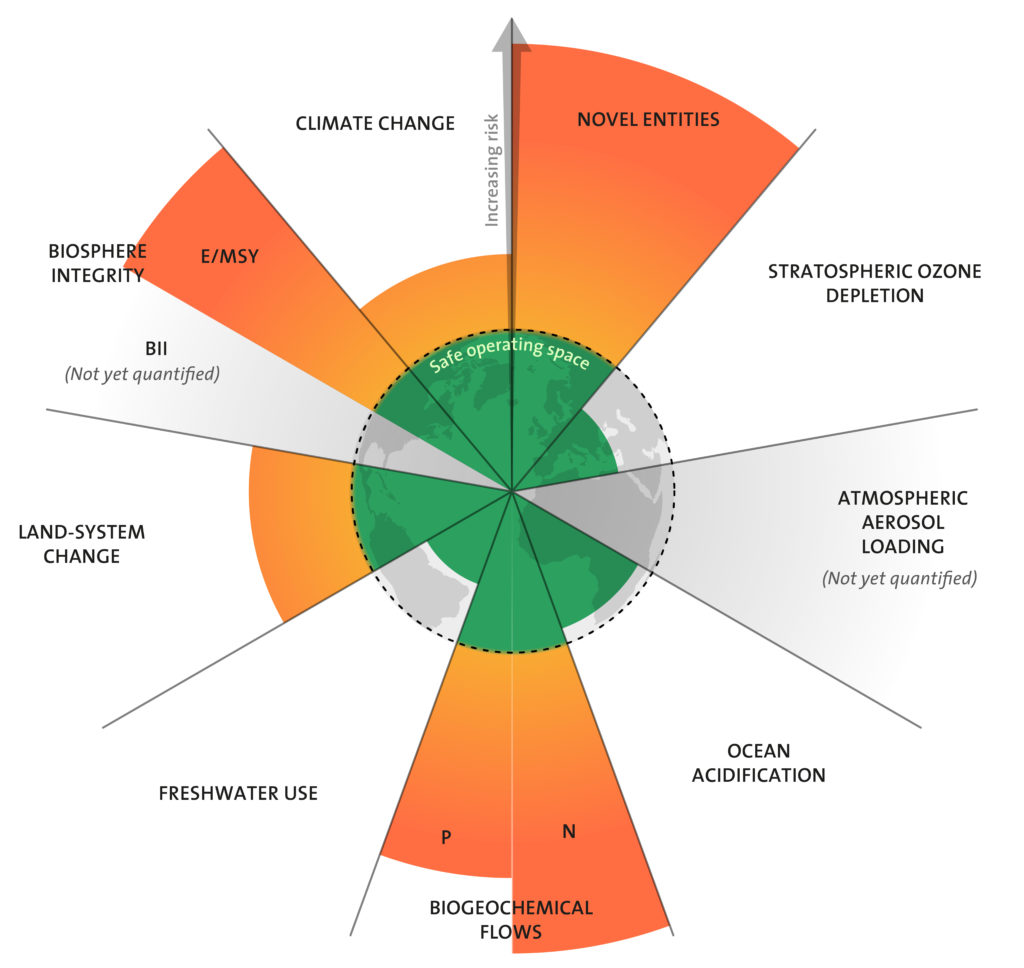

In 2009, the Stockholm Resilience Center identified a set of nine planetary boundaries within which humanity can continue to thrive for generations to come. Climate change is one component of those boundaries, but other components include biosphere integrity, ocean acidification, chemical flows, and the proliferation of novel entities into our environment (e.g., plastics).

Humanity has now exceeded five of those boundaries. In January 2022, novel entities were identified as the most recent boundary to be exceeded.

The Growth Imperative

Why can’t we simply cut back our consumption to lower material use, trash production, and greenhouse gases? To live a dignified life in our society, we must consume to meet our needs and wants–without money we cannot satisfy our needs. And yet that goal line of a dignified life always seems to move. Purchasing a house (a key method of building wealth) is increasingly out of reach, especially with financial institutions entering the market, so we keep renting despite rent rising faster than wages. College, a path to higher income, is less affordable. Healthcare costs are also rising, making retirements less certain. As a result, there is an imperative for us to continue running on the treadmill of incurring debt, working longer, and consuming just to keep up.

The growth imperative is a political and economic phenomenon where the profitability of public companies and the policies of our governments depend on continued economic growth, which is fed by ensuring continual consumption. This imperative structures our society and our choices. For public companies, ensuring continued consumption is critical to maximizing shareholder returns, which some argue is their chief duty. It is in these companies’ interest to find ways to keep us buying their products or monetizing new products.

For governments, tax revenue would decline without continued economic growth, potential resulting in debt defaults. Without economic growth, average Americans would likely see their retirement savings drop.

Is this how a society should be structured?

What is Community Motive?

If the profit motive is the impulse for firms to maximize their profits, then community motive is the impulse for local people to work together to meet basic needs. Not everything we need to consume to have a dignified life should be dependent on market forces or earning money. The growth imperative and its focus on individualized consumption has weakened the community motive, but it still exists: just look at the many examples of mutual aid during the pandemic. Look at the US’s long history of volunteer programs.

We can reimagine a new economy and society. We can break the societal growth imperative and still live happy, dignified, fulfilling lives. We can restore our communities and lower our impact on the environment, hopefully giving future generations a world better than the one we inherited. Communities can do these things with less reliance on our current financial system and on governments.

How can we break the growth imperative that is taken for granted in our society? We need to think about how communities can better provide universal basic services to its members. This idea needs to go beyond simply raising more money for community organizations, though. We need to think about how we can increase community participation in providing these services.

Providing universal basic services means we need to stop thinking about our basic services as commodities—that is, things that must be paid for rather than produced and provided as a universal right. Can we decommodify our basic services, such as food, housing, transport, healthcare, and utilities? In the 21st century, we should not be living in a society where if one lacks money they cannot access these basic services.

(To be clear, it is not necessarily good either to have a society entirely devoid of money. Money is crucial to facilitating exchanges of goods and services, to an extent, and there can be legitimate confusion without an agreed means of exchange. What is not good, however, is when money is necessary for the obtaining of basic services or where societal and financial incentives require continued consumption, despite negative environmental impacts. Community-Led Universal Basic Services is aimed at addressing needs; money can still play a role in meeting wants.)

Further, in today’s society, these basic services are provided through highly technological, complex processes. For communities to more easily provide these services, we must reinvest in convivial technologies—that is, technologies that can be easily learned by most people. Most people could learn how to volunteer on a community farm with a diverse array of locally appropriate produce and even animals; most people would not know how (or want) to work on an industrialized agricultural feedlot.

If our communities can find ways to provide universal basic services through convivial technologies that decommodify basic human needs, then our society may be on its way to breaking the growth imperative, lowering our impacts on the natural environment, and perhaps leading more connected, fulfilling lives.

What might our lives look like if we could spend two or three days a week working to provide community basic services, with the rest of the week to ourselves? We might have more time for family and friends; more time for learning, creativity, and self-exploration; more time to re-connect with art, music, sports, the outdoors, or other activities we might have enjoyed as children.

The most important lesson for public policy analysis derived from the intellectual journey I have outlined here is that humans have a more complex motivational structure and more capability to solve social dilemmas than posited in earlier rational-choice theory. […] Extensive empirical research leads me to argue that […] a core goal of public policy should be to facilitate the development of institutions that bring out the best in humans.” (Elinor Ostrom)

We can come together to provide Community-Led Universal Basic Services (CLUBS). To find out more, please follow these links: